CéramVirginie Boudsocq, self-taught ceramicist, today works hand in hand with France’s most exclusive Michelin-starred restaurants and luxury hotels. Her porcelain creations are entwined with the most original fine-dining experiences She gets to collaborate with a roll call of master chefs, including Emmanuel Renaut, Yannick Alleno and Christopher Hache. For Maison Abelé 1757, the artist looks back on her journey and the unique expertise she has mastered, including some of her collaborations with Michelin-starred chefs, and the hugely demanding alliance of the artistry of the chef and the tableware.

Where and how did you learn this incredibly challenging artform?

To be perfectly honest, I taught myself. I discovered the artform for the first time at a ceramics fair in Anduze in France. Meeting Julie About, an artist who works with ceramics and paper clay, was a revelation.

The minute I got back, I went to buy a block of clay and devoured online tutorials. From firing times to preparing the different types of glaze, I am completely self-taught. Well, almost – with a little help from the Internet (she laughs). It meant I could really, really cram. By learning about porcelain clay this way, I managed to develop a very individual technique to approach my work and the clay. And less influenced by the constraints of classical training.

*Paper clay : terre-papier ou argile cellulosique.

What do you find most compelling about ceramics?

From the very outset, I was drawn to working with my hands; touching the clay, being in close contact, working it and giving it shape. This is something I really love. During my studies at Art School in Cambrai, I was already drawn to Matterist painters, their gestures and strokes.

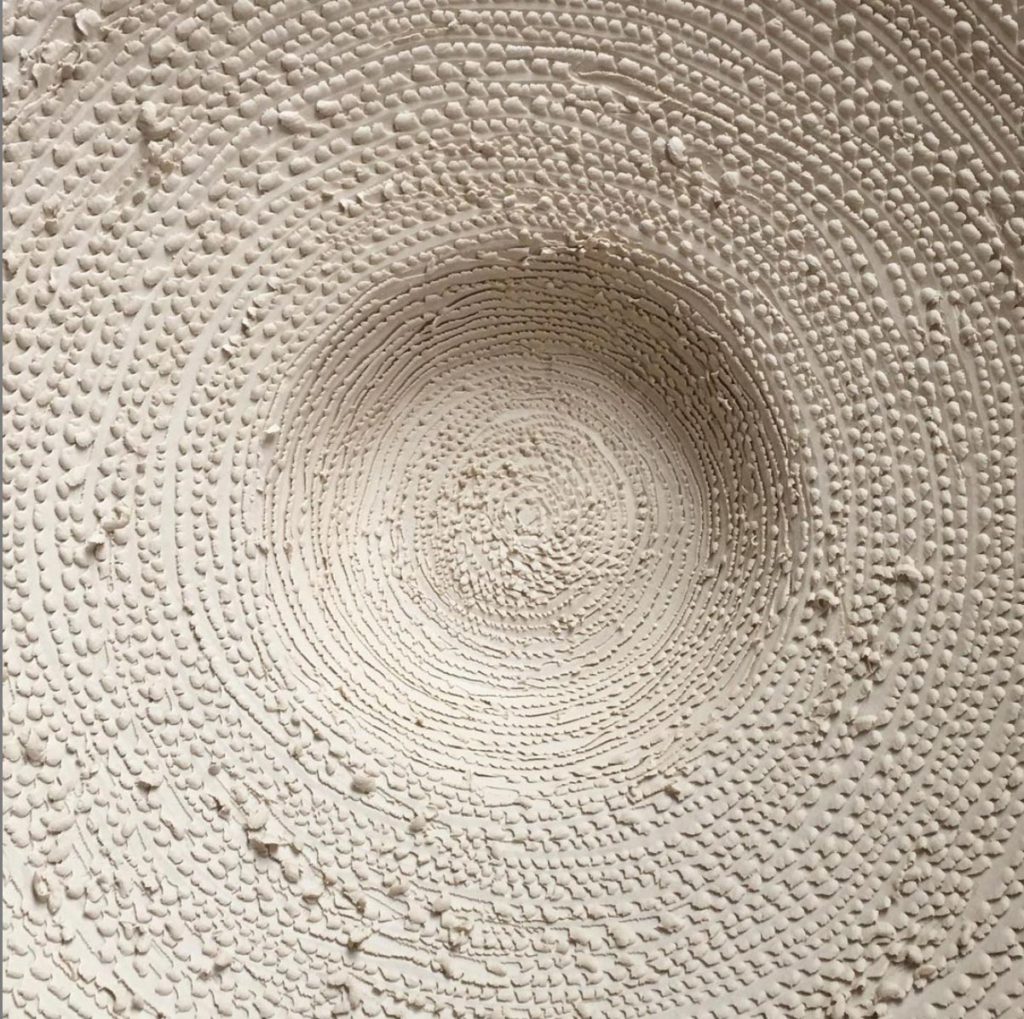

Clay suits me down to the ground and porcelain clay is a real passion. It’s a capricious, challenging material. It’s quite tricky to handle and doesn’t necessarily react as you would expect. What I really like is being able to tear the clay and almost mistreat it. It morphs on its own, without really needing much effort. I also really like the end of the firing stage. Between creating the piece and firing, there is always a surprise.

Sometimes good surprises, like an unplanned twist. Or not quite so good, discovering flaws, breakages and fractures. With clay, the results are never the same. You never stop learning.

In the very early days, I couldn’t understand why people used to say that porcelain clay was clay for the pros. Yet that didn’t stop me buying a block and thinking “We’ll see what happens”.

Your success was immediate. How do you explain this instant recognition from Michelin-starred chefs?

That’s a hard one. Most of it is sheer luck. I started working with clay, and six months later, I was slip casting in plaster molds to make bowls and cups. My kitchen cupboards were crammed full, and I had given cups to all my friends. I needed to do something with it.

One day my husband came home and said: “I know someone opening a home decor store in the south of France, in Saint-Remy-de-Provence, called Maison Marguerite. She loves your work.” I was furious: “I’m not ready. This is madness. I’ve got four measly cups and that’s about it.”

Yet despite everything, I managed to put together some samples. She sold every single piece, including some to Christopher Hache, chef at Les Ambassadeurs restaurant, at Hotel de Crillon in Paris. He and his wife Delphine bought several pieces before commissioning additional orders.

Right from the start we made a huge impact by coming up with a ‘mushroom’ plate for one of his dishes: mushroom mousse served with a very dark crumble. The plate and the food worked in total harmony. It made quite an impression.

When you work for a top restaurant, word of mouth is instantaneous. It inspires other chefs. Yet it still took some time to fall in to place. Working with Michelin-starred chefs is also a lesson in the constraints of fine-dining, the painstakingly exacting standards, what you can get away with, or not. It’s a very different pace to when I first started out. I had to find the right balance between my own way of working and their demands. I had to find the right balance between my own way of working and their demands.

Would you say that it’s you who sculpts the material or the material that drives your creativity?

A bit of both. At the start, I try to explain what I want. I steer the initial steps. But as it fires, it’s up to the clay to bring a certain ‘something’. With porcelain clay, the biggest challenge is knowing where to stop.

For the second firing at high temperature, it’s all down to the materials. You have to know how to allow yourself to be led, without too much intervention. It’s a real joint effort, finding the right balance. Which is what makes porcelain clay so special. It has a mind of its own.

Could you talk us through your artistic approach with your creations for Michelin-starred restaurants?

There are always exceptions, but I love meeting the chefs. It gives me chance to get to know them, understand the food, and taste it too. We are talking hugely talented individuals. I have to capture the essence of their personality from the very first meal. It’s not always easy, but it triggers an idea that takes shape when they want to showcase a particular signature dish.

For his Japanese restaurant “L’Abysse”, Yannick Alleno was looking for something very handcrafted and unique. We discussed the contents of the menu and the serveware required for the dishes. T The name of the restaurant gave me the idea of a kind of movement that would rise from the depths of the ocean in three stages: the first with a dish crafted from clay, evoking pieces of coral. Then, a sort of upwards motion like bubbles rising to the surface. And lastly, the lapping of water at the water’s edge.

Ideas often come to the fore during conversations with the chef, for the serveware, the ingredients and the particular emotions we have to convey.

It was the same process for the mushroom plate. Christopher Hache explained he was working with one of the last mushroom farms in Paris for one of his dishes. This is how I got the idea of an upside-down mushroom, with a dome forming the base. And in a stroke of luck, the proportions were spot on straight away. Up until now, touch wood, these exchanges with the chefs have always worked well.

Ceramics follow a series of carefully defined steps before taking form. How much time is required from initial idea to delivery of the final piece?

It really varies and depends on everyone’s availability. Creating the piece itself can be relatively quick. In terms of preparatory steps, there is very little to do other than a few rough sketches. And yet, from sketch to finalised piece, so much happens in between.

Depending on the weather, a piece of tableware can take between 8-10 days to dry before undergoing two separate firings. . Normally, it takes 3-4 weeks to get a prototype worth its salt. If everything goes according to plan i.e. the prototype doesn’t break, and the glaze takes, even the most minor modification can add an additional three weeks at least. Added to which, it takes 2-3 months to make 40-50 items. So generally, from the moment of commencing the prototype, the final sign-off and the production stage itself, it can take six months.

Could you explain how your creative works are an integral part of the gastronomic experience?

There are really several ways of looking at it. Some chefs believe, quite rightly, that it’s all about the recipe, in which case my input is almost irrelevant. Others are looking for an overall aesthetic where the serveware elevates the food to another plain. In this case, they come to me to create another level of emotion. There are really two schools of thought. Yet simplicity works well too.

To engage with some chefs I have to imagine that our collaboration is inspirational for them too. They sometimes want to use the serveware to enhance their food. And when this works, it’s very special. Recently I created a mushroom plate for Emmanuel Renaut for one of his starters. Together they really created something special. If this particular dish had been served on plain crockery, the final outcome would have been totally different.

For diners coming to the restaurant, there is an added level of interest. The perception of experiencing something quite extraordinary; the serveware is handcrafted, a total one off, while the dish itself has been created by a seasoned master chef who knows how to cook the ingredients to perfection. There is a wonderful harmony between the food and the crockery..

Nowadays, chefs pay considerably more attention to the tableware in their restaurants. This can be another way of stamping their signature on a dish. Creating for 3-starred Michelin establishments essentially helps them affirm their food and personality. Whether Michelin-starred or not. This trend simply didn’t exist twenty years ago and has continued to gain traction in recent years.

Learn more about Virginie Boudsocq’s work on olgaetc.com and on her Instagramhandle.

Texte – Geoffrey Chateau | Photo – Virginie Boudsocq