Philippe Mille, resident chef at prestigious 2-star Michelin Domaine les Crayères, is among the modest and talented chefs of French gourmet cuisine. Having excelled in the kitchens of France’s finest dining establishments, including the Drouant, the Pré Catelan, the Ritz and Le Meurice, this Meilleur Ouvrier de France is now Group Executive Chef at Domaine Les Crayères, overseeing the kitchens at both 2-star Michelin Le Parc, and Le Jardin restaurants. For Abelé 1757, Champagne’s adoptive son looks back at his love for the Champagne-Ardenne terroir and the importance of taking time in the kitchen.”

What is your signature cooking style?

A style reflecting the soils, that we go to great lengths to recreate. I focus deep down in the roots to capture the true spirit of the product. Without quite literally adding soil into my dishes, this is the identity that I strive to recreate in my cooking. Really dig down into the roots and understand where they draw their DNA. There may also be clay or wood; basically a whole host of materials at my fingertips to enhance my food.

How do you incorporate this ‘soil signature’ into your culinary creations?

By recreating it, quite simply. 45 million years ago, Champagne was completely under the sea. With chalk, I try to showcase this saline quality. For me, Chardonnay delivers this identity. It’s a grape variety with lots of impact that I tend to serve with razor clams or cockles. I also enjoy playing with the image of the white chalk with black and white. It all makes sense with the two colours side by side.

Does time influence your cooking?

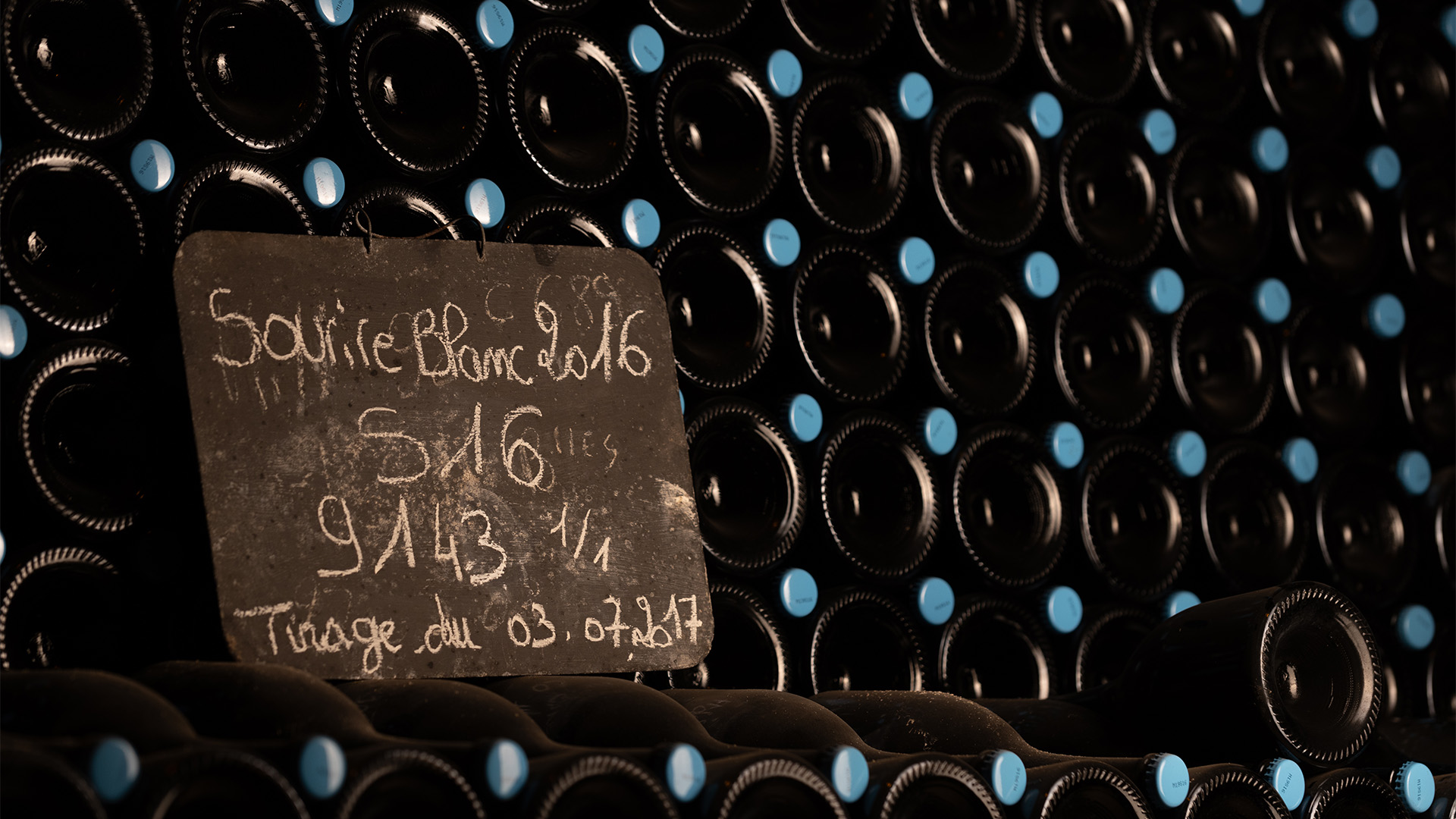

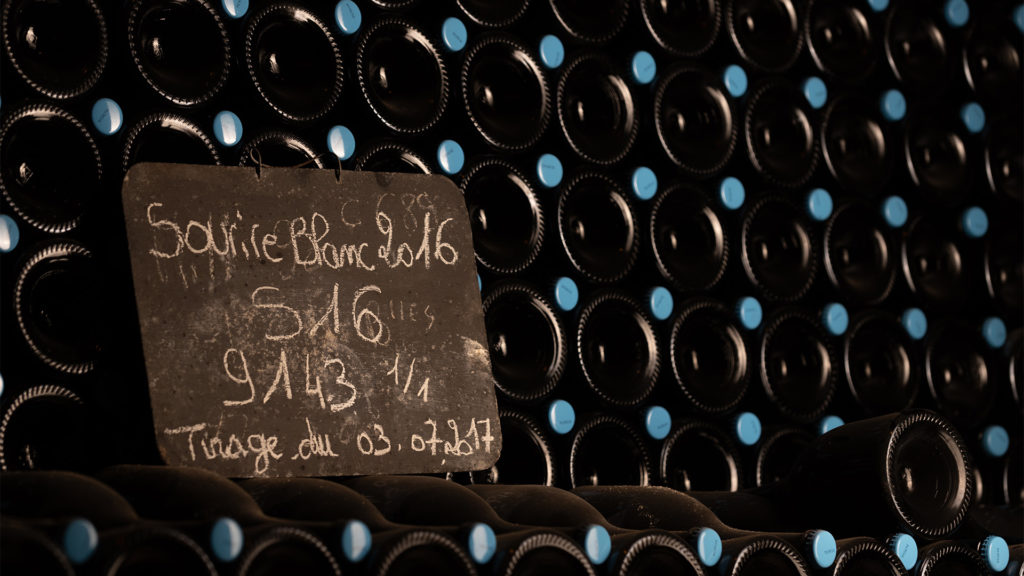

Like many chefs, I work on food and champagne pairings. But my approach is more focused on the barrel, and more specifically, on the wooden staves used to make the barrels in Champagne. These barrels are constructed from ancient oak trees that can be 120, 200 or even 300 years old in some cases. They are dried for several years before being shaped into barrels. The champagne will absorb this wood for the best part of 20, 30, 40 or even 50 years in some cases.

I wanted this story to continue by incorporating the wooden staves into my cuisine. At the moment my main focus is fish. I am looking to recreate this exchange, this historic transmission. Not only the exchange of time with the fish, but also between the raw materials and flavours.

You mentioned artisans. What is their role in your cooking?

Artisans and producers are absolutely key. I currently work with 64 in total over the course of the year, depending on the season. Seasonality, once again, is essential, as is working with the seasons. On me demande souvent « Combien de fois changez-vous votre carte sur une saison ? ». La vraie question serait plutôt « Combien de fois je change les produits ? ». The ingredients are key and shape my dishes.

Over the course of the year I may have to change the menu 60-70 times if I remove a product that I feel is no longer at its best to be served to our clientele. It’s also about respecting nature.

What would be your greatest memory working with these producers?

One of my fondest memories dates back around ten years ago, to Mme Bernier and her saffron. A long time ago now, she turned up at Domaine les Crayères with a small vial, like the type you find at the chemist, and inside there were a few threads of saffron. She explained that she had inherited some land and had decided to plant saffron crocuses. She wanted me to taste her harvest and give her some honest feedback. Her saffron was no better or worse than any other saffron it was the provenance I was interested in, and its identity in relation to a unique, specific terroir.

Like Champagne, we decided to harvest one vintage per year. We now have almost a kilo of saffron to work with and a harvest that can be used all year round. People have no idea what this actually entails. A kilo of saffron is huge if you consider the weight of a single thread. Every harvest brings a new dimension to the saffron; depending on the weather, it could be more intense or more floral. I have to continually adapt depending on the aromas. Some of the recipes featured last year will have to change as the saffron is totally different.

We have to progress and nature guides us every step of the way; subjecting us to snow, hail and sunshine, and all these elements play a role.

How do you communicate and share your experience of French gastronomy?

My approach to sharing this experience works on a number of levels. Firstly, from chef to chef, chef to commis chef or chef to staff. Also sharing through the cookery books I collect. Obviously, not everything is relevant today, but the basics remain the same, which is the important part. You have to understand the attitudes at the time regarding products and the seasons. 200 years ago, truffles featured in every dish. Today it’s a luxury. It’s much easier to understand when you have the background knowledge.

And then there’s handing down from person to person. I try to share as much as possible with my teams. It’s really important for me. Certain professions have been around for centuries, which we need to preserve, but also move with the times. Knowledge and know-how are as important as existence.

So how does a chef spend his time when not in the kitchen?

He gets out of the kitchen! (laughs). Sport, the great outdoors, walks in the forest. Just taking time to soak it all in, to watch and learn. I also enjoy drawing, museums and art in every form. I like art because I appreciate the different forms such as sculpture, painting and architecture. Arts and crafts and anything created by the Human hand. But all this is intrinsically linked to my profession.

Writer- Geoffrey Chateau | Photo copyright – Anne-Emmanuelle Thion