Since 1874, the Geay family has developed an undying love affair for a precious shellfish: the Pacific or ‘creuse’ oyster. Located in the dainty fishing port of La Tremblade, in the heart of the Charente basin, five generations of the Geay family have pursued the tradition of farming premium quality oysters. For Champagne Abelé 1757, Adrian Geay, a young, innovative artisan with a true passion for his work, provides an insight into the natural balance that has shaped oysters for centuries.

Could you introduce yourself and take us back through the history of the Geay family?

I’m Adrien, and a fifth generation oyster farmer in the Geay family. Our entrepreneurial story goes back to my great-great-grandfather working in the region’s markets. Since that time, each generation has done its bit to grow the business, from increasing production to developing sales in northern France, and then nationwide. Since joining the company, we have expanded outside France. All in all, our oysters are sold in more than 70 countries. Oysters have a great reputation around the globe.

I’m from the Charente region and the ocean has always been part of my life. This is why I love being an oyster farmer; working with a natural product in a magnificent setting, with as little intervention as possible, everything done by hand. I am totally in my element.

Our work relies entirely on the natural conditions dictated by the ocean. And this is what makes our profession so unique. Good or bad, every day has a surprise in store. Essentially, we market a nutritious product that ticks the environmental box too. Oysters are arguably the perfect organism.

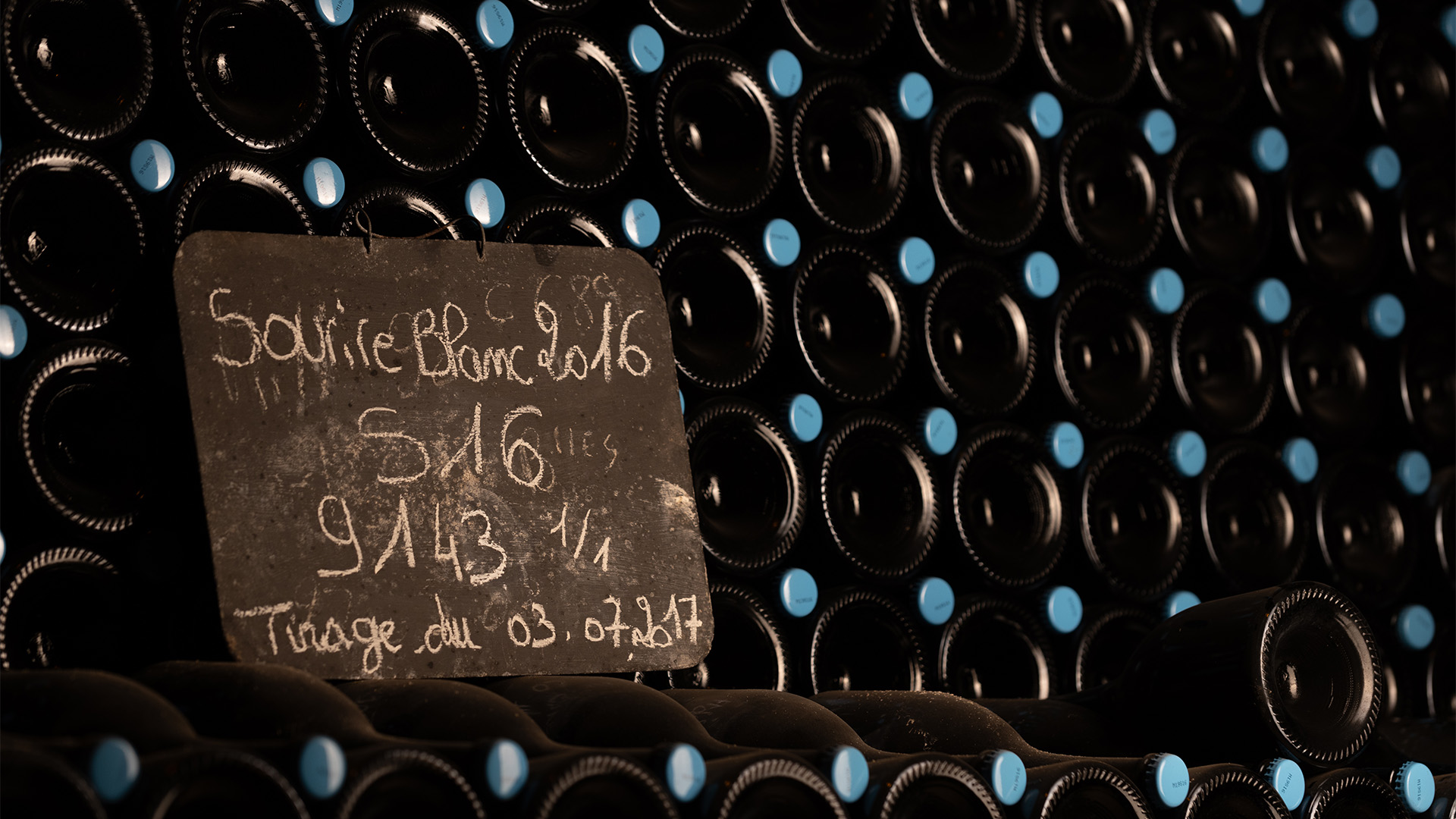

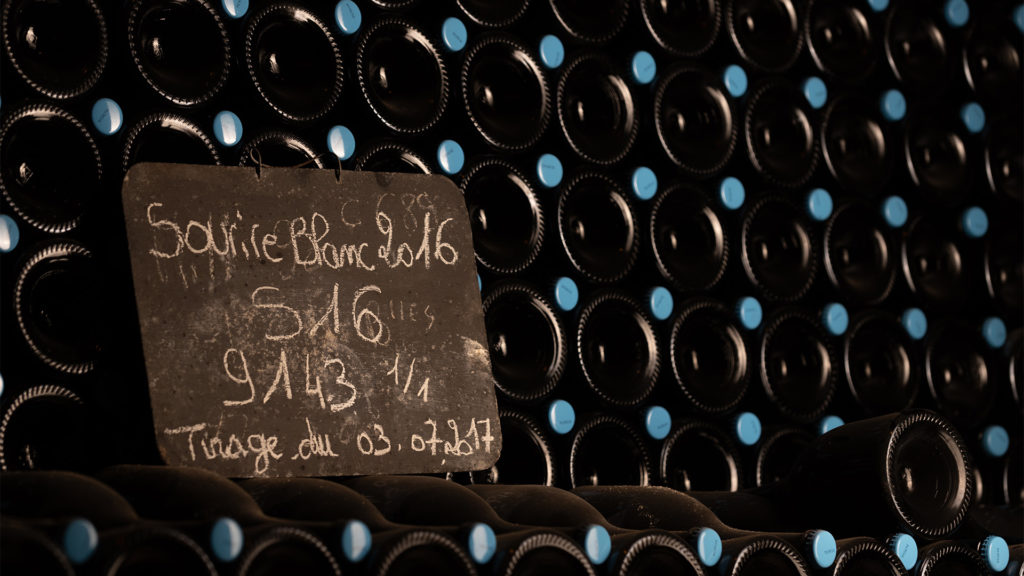

Just like champagne, which requires several years cellar-ageing to reach its true potential, what are the essential stages, and how long does it take to produce a quality oyster?

The first stage is collecting the spat. The Marennes-Oléron basin is unlike anywhere else in the world. For a short time – from late July to the beginning of August – the oysters spawn. Large quantities of larvae float around for 10-15 days before finding somewhere to settle.

And it is at this exact moment that we set out our racks to collect them. Nine months later, the ‘spats’, as they are known at this stage, are about the size of a fingernail. They are then detached from the racks and commence the growing period in mesh bags, which are tumbled and turned over a period of several months.

It takes two to five years in total to produce a single oyster. During this time, the oysters never stop developing. It’s up to us as oyster farmers to slow down the process, and to do this we regularly turn and tumble the oysters. This helps break down soft shell growth and helps make the shell as round or deep-cupped as possible. Aside from the aesthetic value, tumbling also encourages the oysters to channel their energy into making the flesh more succulent, rather than the shell.

At Geay, we produce two types of oyster. Firstly, the ‘fines de claires’, which are less fleshy than other oysters, finished in ‘claires’ or salt ponds, and present immediate briny flavours, not particularly chewy and quite short on the palate. They take two and a half to three and a half years to produce.

Then there’s our special oysters. These are more mature and take three to five years to reach market size. They are the exact opposite of fines de claires: they grow slowly, have a harder shell, while the meat is much fleshier with a pronounced briny flavour and impressive length on the palate, lasting between several and ten minutes.

As a rule of thumb, the quicker the oyster grows, the more delicate it tends to be. The more time you allow, the larger it gets. Once the first growth stage complete, the oysters are graded by size and ‘affiné’ or aged in oyster parks.

We sometimes hear oystermen referred to as the gardeners of the sea. Why is this profession so unique?

Whether it’s our particular location or terroir, or our skilled expertise, there’s nothing quite like it anywhere else in the world. Give me an oyster and I can tell you everything there is to know, including where exactly it was reared, just by looking at the shell.

To give you a comparison, the lines on the shell are like rings on a tree; each variation in colour relates to a specific growth period. If you look really carefully, you can tell if the park was greatly exposed to the sea, with the shell often whiter and smoother as a result. In contrast, the parks located higher along the river reveal fewer markings.

This is the real beauty of our profession. On the one hand, many long hours out in the field honing the skills of the trade, and on the other, the magic of sharing our product with a customer on the other side of the planet. It’s all the motivation we need to constantly improve our oysters and make them the best they can be to guarantee their unique flavour.

What are the values that shape your work on a daily basis?

Respect is paramount; respecting the product, and respecting the local environment, from the quality of the water, which is critical in our profession, to recycling waste. We can now say that our oyster shells are 100% recycled and repurposed to give life to other objects, such as spectacles, tarmac and paints. It’s important for my generation to learn to recycle as much waste as possible.

Also respecting and protecting our patrimony and specialist skills. You can’t put a value on family legacy. At the same time, it is important to know how to move with the times and constantly improve product quality, and working practices too.

After so many years, to what do you attribute the reputation of Geay oysters?

Our reputation stems from our skilled expertise and many years invested in producing a range of premium quality, special oysters. The ‘Geay special’ is our most popular oyster around the world. It’s fleshy and crisp with lingering flavours. It’s the number one choice for oyster aficionados.

Then there’s also one of my speciality oysters, ‘la friandise’ which is a much smaller oyster, specially cultivated to enjoy as an aperitif. It goes particularly well with champagne. And finally, there’s the ‘Sublime’. It’s fleshy with a lovely green colour.

How have oyster production methods evolved since the first generation?

Production methods have moved on dramatically. Our equipment to start with. In the past, oyster farmers would travel to parks by sailing boat. Basically these were tall ships that were difficult to handle in high winds. Then with the advent of motorisation,

it only took a day to work on the oyster park. Gradually these boats were phased out and replaced by much lighter, flat-bottomed, aluminium barges, which are easier to handle and more energy-efficient. Ecologically, it’s also a revolution of sorts, as it reduces the need to paint them so regularly.

Production has also moved with the times. In the past, oysters were placed flat on beds separated by small grids. This exposed the oysters to huge problems with predators. And with the slightest breeze, the shells would disperse in all directions.

To solve these issues, we switched to production in raised mesh bags, which are a much more efficient method of tumbling the shells to break down the outer shell. As producers, working conditions have improved for all of us as a result, there’s no question.

The decline in mortality rate is also a key factor. In winter, previous generations transported their oysters by rail. Though this was fine in winter, high summer temperatures were a challenge. With the arrival of cold chain transport, oysters can be conserved for much more extended periods. It’s a significant advantage, and we now dispatch our oysters all over France, even worldwide.

How do oysters develop their flavour properties?

Every region has its differences and each park its particular terroir. Oyster production is exactly the same as making champagne. The climate also affects quality; if it rains, the oysters will be sweeter, and with too little rain, the oysters tend to be saltier. Sometimes, all the conditions stack in our favour and the oysters fatten up in just two months’ time, becoming full and fleshy.

On a more personal note, what is your relationship with time?

I hate standing still. I want things to move at pace, with lots going on. Yet my profession as an oysterman can be quite tying. It takes several years for an oyster to reach full maturity. You can’t fast-forward the clock, and I use this time to reflect on production methods and what we can change to attain pristine quality.

Some see oysters as Nature’s watchmen. Could you expand on this?

Oysters are great at sequestering carbon. It takes ten kilos of oysters to absorb the same amount of carbon as the emissions from a train journey from Bordeaux to Paris. The shells are also amazing at filtering water. Trials in the bay of New York have run for several years testing the ability of oyster shells to purify turbid water (Note from the editor: cloudy).

Whether silt or waste, the oysters filter any pollution, which is then absorbed into the shells and expelled as waste. After several months the water becomes completely clear.

Just by existing, oysters enhance their surroundings. As a result of the raised beds, fauna and flora are more prevalent in our parks than previously; fish feed on sediment, while other species seek refuge and breed. It will take some careful calculations, but we truly believe that oyster production has a neutral impact on the environment. It’s a remarkable opportunity.

Your oysters are certified ASC, AB, Marennes-Oléron and Label Rouge. For you, how important is it being awarded these quality labels?

Over the years we have been awarded many labels, including Label Rouge, Organic, ASC farm standard, Marennes-Oléron and Global Cap. All these certifications provide a guarantee to our customers regarding the promises we make and the consistency of our approach. This builds a firm relationship of trust with consumers and ensure there is no doubt regarding our approach. When we talk to customers, we realise these labels provide quality reassurance relating to our products and what they eat. Essentially, they see our business in another light.